This week I have watched a video about body language. My work for this semester to create a character animation that focuses on personality presentation through the body language.

I have researched the definition and some reflection of body language.

Body language have been defined by FBI that nonverbal communications—facial expressions, gestures, physical movements (kinesics), body distance (proxemics), touching (haptics), posture, even clothing—to decipher what people are thinking, how they intend to act, and whether their pronouncements are true or false.

WHAT EXACTLY IS NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION?

Nonverbal communication, often referred to as nonverbal behaviour or body language, is a means of transmitting information—just like the spoken word—except it is achieved through facial expressions, gestures, touching (haptics), physical movements (kinesics), posture, body adornment

(clothes, jewelry, hairstyle, tattoos, etc.), and even the tone, timbre, and volume of an individual’s voice (rather than spoken content). Nonverbal behaviours comprise approximately 60 to 65 percent of all interpersonal communication and, during lovemaking, can constitute 100 percent of communication between partners (Burgoon, 1994, 229–285).

Nonverbal communication can also reveal a person’s true thoughts, feelings, and intentions.

In order to ensure our survival, the brain’s very elegant response to distress or threats, has taken three forms: freeze, flight, and fight.

Freeze action

This freezing action is sometimes termed the “deer-in-the-headlights” effect. When suddenly caught in a potentially dangerous circumstance, we immediately freeze before taking action. In our day-to-day life, this freeze response manifests innocently, such as when a person walking down the street stops suddenly, perhaps hitting himself on the forehead with the palm of his hand, before turning around and heading back to his apartment to turn off the stove. That momentary stop is enough for the brain to do some quick assessing, whether the threat comes in the form of a predator or of a thought remembered. Either way, the psyche must deal with a potentially dangerous situation (Navarro, 2007, 141– 163).

We not only freeze when confronted by physical and visual threats, but as in the example of the late-night doorbell, threats from things we hear (aural threats) can also alert the limbic system. For instance, when being chastised, most people hold very still. The same behaviour is observed when an individual is being questioned about matters that he or she perceives could get them into trouble. The person will freeze in his chair as if in an “ejector seat” (Gregory, 1999).

Another way the limbic brain uses a modification of the freeze response is to attempt to protect us by diminishing our exposure.

The “turtle effect” (shoulders rise toward the ears) is often seen when people are humbled or suddenly lose confidence.

Flight response

When the freeze response is not adequate to eliminate the danger or is not the best course of action (e.g., the threat is too close), the second response is the flight response. Obviously, the goal of this choice is to escape the threat or, at a minimum, to distance oneself from danger.

Some of the “evasive” actions take to distance from the unwanted attention of others. For example a child turns away from undesirable food at the dinner table and shifts her feet toward the exit, an individual may turn away from someone she doesn’t like, or to avoid conversations that threaten her. Blocking behaviours may manifest in the form of closing the eyes, rubbing the eyes, or placing the hands in front of the face.

The Fight Response

COMFORT/DISCOMFORT AND PACIFIERS

Adopt more discreet and socially acceptable ways to satisfy the need to calm ourselves (e.g., chewing gum, biting pencils).

Types of Pacifying Behaviours

Pacifying behaviours take many forms. When stressed, we might soothe our necks with a gentle massage, stroke our faces, or play with our hair. This is done automatically. Our brains send out the message, “Please pacify me now,” and our hands respond immediately, providing an action that will help make us comfortable again.

Rubbing of the forehead is usually a good indicator that a person is struggling with something or is undergoing slight to severe discomfort.

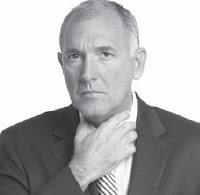

Neck touching takes place when there is emotional discomfort, doubt, or insecurity.

Cheek or face touching is a way to pacify when nervous, irritated, or concerned.

Exhaling with puffed out cheeks is a great way to release stress and to pacify. Notice how often people do this after a near mishap.

Men adjust their ties to deal with insecurities or discomfort. It also covers the suprasternal notch.

If a stressed person is a smoker, he or she will smoke more; if the person chews gum, he or she will chew faster. All these pacifying behaviours satisfy the same requirement of the brain; that is, the brain requires the body to do something that will stimulate nerve endings, releasing calming endorphins in the brain, so that the brain can be soothed (Panksepp, 1998, 272). Men prefer to touch their faces. Women prefer to touch their necks, clothing, jewelry, arms, and hair.

Pacifying Behaviours Involving the Neck

Neck touching and/or stroking is one of the most significant and frequent pacifying behaviours we use in responding to stress.

Men typically cover their necks more robustly than women as a way to deal with discomfort or insecurity.

Even a brief touch of the neck will serve to assuage anxiety or discomfort. Neck touching or massaging is a powerful and universal stress reliever and pacifier.

Women pacify differently. For example, when women pacify using the neck, they will sometimes touch, twist, or otherwise manipulate a necklace, if they are wearing one.

Pacifying Behaviours Involving the Face

Touching or stroking the face is a frequent human pacifying response to stress. Motions such as rubbing the forehead; touching, rubbing, or licking the lip(s); pulling or massaging the earlobe with thumb and forefinger; stroking the face or beard; and playing with the hair all can serve to pacify an individual when confronting a stressful situation.

Pacifying Behaviours Involving Sounds

Whistling can be a pacifying behaviour. Some people whistle to calm themselves when they are walking in a strange area of a city or down a dark, deserted corridor or road. Some people even talk to themselves in an attempt to pacify during times of stress. Some behaviours combine tactile and auditory pacification, such as the tapping of a pencil or the drumming of fingers.

Excessive Yawning

Sometimes we see individuals under stress yawning excessively. Yawning not only is a form of “taking a deep breath,” but during stress, as the mouth gets dry, a yawn can put pressure on the salivary glands.

The Leg Cleanser

The Ventilator

The Self-Administered Body-Hug

When facing stressful circumstances, some individuals will pacify by crossing their arms and rubbing their hands against their shoulders, as if experiencing a chill. It is a protective and calming action we adopt to pacify ourselves when we want to feel safe.

NONVERBAL BEHAVIORS INVOLVING THE FEET AND LEGS

Happy feet are feet and legs that wiggle and/or bounce with joy. When people suddenly display happy feet—particularly if this occurs right after they have heard or seen something of significance—it’s because it has affected them in a positive emotional way.

You don’t need to look under the table to see happy feet. Just look at a person’s shirt and/or his shoulders. If his feet are wiggling or bouncing, his shirt and shoulders will be vibrating or moving up and down. These are not grossly exaggerated movements; in fact, they are relatively subtle. But if you watch for them, they are discernible.

Second, moving feet and legs may simply signify impatience. Our feet often jiggle or bounce when we grow impatient or feel the need to move things along. Watch a class full of students and notice how often their legs and feet will twitch, jiggle, move, and kick throughout the class. This activity usually increases as the class draws to a close. More often than not, this is a good indicator of impatience and the need to speed things up, not a sign of happy feet. Such activity reaches a crescendo as dismissal time approaches in my classes. Perhaps the students are trying to tell me something.

When Feet Shift Direction, Particularly Toward or Away from a Person or Object

Assume you are approaching two people engaged in a conversation. These are individuals you have met before, and you want to join in the discussion, so you walk up to them and say “hi.” The problem is that you’re not sure if they really want your company. Is there a way to find out? Yes. Watch their feet and torso behavior. If they move their feet—along with their torsos—to admit you, then the welcome is full and genuine. However, if they don’t move their feet to welcome you but, instead, only swivel at the hips to say hello, then they’d rather be left alone.

When two people talk to each other, they normally speak toe to toe. If, however, one of the individuals turns his feet slightly away or repeatedly moves one foot in an outward direction (in an L formation with one foot toward you and one away from you), you can be assured he wants to take leave or wishes he were somewhere else. This type of foot behavior is another example of an intention cue (Givens, 2005, 60–61).

Where one foot points and turns away during a conversation, this is a sign the person has to leave, precisely in that direction. This is an intention cue.

The Knee Clasp

Clasping of the knees and shifting of weight on the feet is an intention cue that the person wants to get up and leave.

Gravity-Defying Behaviors of the Feet

Leg Splay

Feet/Leg Displays of High Comfort

We normally cross our legs when we feel comfortable. The sudden presence of someone we don’t like will cause us to uncross our legs.

Significant Change in Intensity of Foot and/or Leg Movement

No comments:

Post a Comment